Laccaria bicolor

a mutualistic fungus and

pioneer in genome sequencing

Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for August 2010

by Todd Osmundson and Tom Volk.

Please click

TomVolkFungi.net for the rest of Tom Volk's pages on fungi

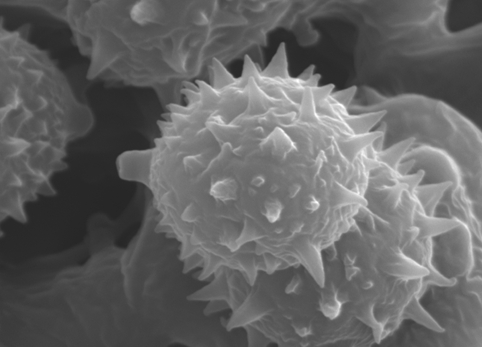

Laccaria bicolor and other Laccaria species are distinguished by having white spore prints, spiny (echinulate) basidiospores, thickened but non-waxy gills, and orange, pinkish-orange, brown, or violet coloration (though a recently-described species,

Laccaria alba, is described as being white or whitish). Laccaria identification in the field can be tricky due to fact that many features of the basidiome (mushroom) are

similar between different species (for example,

Laccaria species don’t come in very many colors), but can be quite variable

within species (for example, colors often vary in hue between individual mushrooms

and often exhibit fading in age, and basidiome size can also vary significantly). Positive identification often requires careful observation of microscopic features such

as spore size and shape, the length and width of the spines on the spores, the number of sterigmata on the basidia (2 or 4), and the microscopic arrangement of

the cells on the surface of the cap. The most commonly encountered species of Laccaria – if the field guides, scientific literature, and foray records are correct –

is Laccaria laccata; however, because of the low number of distinguishing field characters in the genus, this name tends to be applied to almost any

Laccaria with

orange to orange-brown basidiomes. Additional examination of collections called L. laccata commonly uncovers less well-known species hiding therein.

Laccaria bicolor

is distinguished from L. laccata by having violaceous gills and violet mycelium at the base of the stem; however, these violaceous and violet colors fade

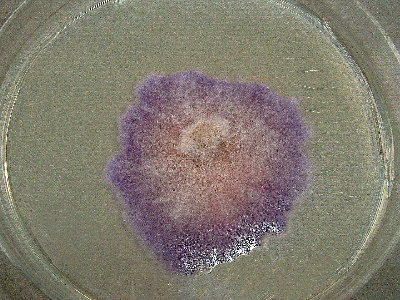

rather quickly in age (such as in the mushrooms below and to the right), so that older individual sporocarps can be easily mistaken for L. laccata. However, a tissue culture on potato dextrose agar leaves no

doubt between the two species: L. laccata tissue develops white mycelia in culture, and the mycelia of L. bicolor are a stunning bright violet (but, as in the sporocarp,

the violet color also fades fairly rapidly in culture). If you don’t have the equipment or the inclination to take tissue cultures, a trick that sometimes works is to

put a couple of fresh sporocarps in a paper bag in the refrigerator and leave them for a day or two; new mycelial growth will often occur at the base of the stem,

producing violet colors in L. bicolor but not L. laccata. Laccaria bicolor is also difficult to distinguish from two close relatives,

L. nobilis and L. trichodermophora, which both contain violaceous mycelial colors.

For more information on telling these species apart, see the outstanding website on Laccaria by Dr. Gregory Muellerhttp://www.fieldmuseum.org/research_collections/botany/botany_sites/fungi/index.html.

One of the fascinating pre-genomic discoveries about L. bicolor (by Dr. John Klironomos, currently at the University of British Columbia-Okanagan, and colleagues) was that it could obtain nitrogen by killing and consuming springtails – tiny arthropods that live in soil – thus functioning in a dual role as both an EM partner and a soil predator/decomposer.(Klironomos and Hart, 2001. Food-web dynamics: Animal nitrogen swap for plant carbon. Nature 410, 651-652, doi:10.1038/35070643) These insights have been confirmed by the finding of genes within the

L. bicolor genome that encode enzymes capable of breaking down proteins found in plant litter and soil animals.

As scientists continue to study Laccaria bicolor in vitro (i.e., in the laboratory) and its genome “in silico” (i.e., in computers), additional discoveries about the EM symbiosis and its molecular underpinnings will result.

An additional ectomycorrhizal fungal genome, that of the Perigord Black truffle (Tuber melanosporum) has now been sequenced, and several others (including

Lactarius quietus, Hebeloma cylindrosporum, Boletus edulis, Rhizopogon salebrosus, Paxillus involutus, Pisolithus microcarpus, Pisolithus tinctorius, Amanita thiersii, Amanita muscaria, and

Amanita bisporigera) are currently in progress. Comparison of these genomes with that of

L. bicolor will not only deepen the insights gained from L. bicolor, but should shed light on topics such as how different groups of fungi evolved the EM lifestyle and how host specificity (the range of plant partners with which a given EM fungus can associate) is controlled.

We hope you enjoyed learning about Laccaria bicolor, the first ectomycorrhizal mushroom of the genomic era. Perhaps the beautiful violet mycelium of this species will inspire a certain Fungus of the Month author when he chooses his next hair color! This page was last updated August 9, 2010

Learn more about fungi! Go to Tom Volk's Fungi Home Page --TomVolkFungi.net Return to Tom Volk's Fungus of the month pages listing

This month’s fungus is Laccaria bicolor, a mycorrhizal member of the Basidiomycota. Of course mycorrhizae (literally "fungus roots") are mutually beneficial relationships between fungi and plants-- the fungus gets sugars from photosynthesis while supplying the plant with essential minerals and increased water uptake. Laccaria bicolor was the first mutualistic fungus to have its entire genome sequenced.

The completion of the 65 million base-pair genome sequence (about 43 times smaller than the 2.8 billion base-pair human genome) was announced in March, 2008 by Francis Martin and colleagues in a paper in the scientific journal Nature (Nature 452:88-92, 2008, doi:10.1038/nature06556).

In celebration of the 2.5-year anniversary of the genome announcement, and because Todd just found out that he’ll be rooming with Tom at the 50th Anniversary NAMA Foray (and chances are good that Tom would ask what became of this long-ago-promised FotM), the time is right to recognize this groundbreaking ectomycorrhizal mushroom with its own Fungus of the Month page.

Long before its genome was sequenced, L. bicolor was a favorite species for researchers studying ectomycorrhizal (EM) fungi. Unlike most other EM fungi,

L. bicolor can be grown in culture (from basidiospores or tissue samples) and paired with the roots of its mycorrhizal partner trees (pines and other conifers) in the laboratory, allowing studies of its physiology, biochemistry, and interaction with its plant partner to be studied under controlled conditions. Because most EM plants do not grow well, if at all, without EM fungi,

L. bicolor has also been widely used in forestry to colonize the roots of conifer trees prior to outplanting.

Long before its genome was sequenced, L. bicolor was a favorite species for researchers studying ectomycorrhizal (EM) fungi. Unlike most other EM fungi,

L. bicolor can be grown in culture (from basidiospores or tissue samples) and paired with the roots of its mycorrhizal partner trees (pines and other conifers) in the laboratory, allowing studies of its physiology, biochemistry, and interaction with its plant partner to be studied under controlled conditions. Because most EM plants do not grow well, if at all, without EM fungi,

L. bicolor has also been widely used in forestry to colonize the roots of conifer trees prior to outplanting.

Laccaria, along with the false truffle Hydnangium and the half-sequestrate

Podohydnangium (both of the latter resembling truffles or puffballs), often used to be placed with other white-spored agarics in the family Tricholomataceae; however, some authors placed these genera in a separate family, Hydnangiaceae, on the basis of their distinct spore type. DNA studies tell us that Hydnangiaceae is indeed distinct from Tricholomataceae, but have thus far been unable to resolve where exactly this family belongs in the fungal family tree. A recent study by Dr. Brandon Matheny and colleagues (Matheny

et al., 2006. Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview. Mycologia 98(6):982-995) placed Hydnangiaceae as a relative of Psathyrellaceae (the family that includes the dark-spored genera

Psathyrella, Coprinopsis, and Coprinellus), but this position was not strongly supported by the data.

Laccaria and its relatives, with their unique basidiospore morphology, therefore remain a taxonomic enigma.

Laccaria, along with the false truffle Hydnangium and the half-sequestrate

Podohydnangium (both of the latter resembling truffles or puffballs), often used to be placed with other white-spored agarics in the family Tricholomataceae; however, some authors placed these genera in a separate family, Hydnangiaceae, on the basis of their distinct spore type. DNA studies tell us that Hydnangiaceae is indeed distinct from Tricholomataceae, but have thus far been unable to resolve where exactly this family belongs in the fungal family tree. A recent study by Dr. Brandon Matheny and colleagues (Matheny

et al., 2006. Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview. Mycologia 98(6):982-995) placed Hydnangiaceae as a relative of Psathyrellaceae (the family that includes the dark-spored genera

Psathyrella, Coprinopsis, and Coprinellus), but this position was not strongly supported by the data.

Laccaria and its relatives, with their unique basidiospore morphology, therefore remain a taxonomic enigma.

Several Laccaria species, including L. laccata, L. bicolor, and L.

amethystina, have been reported to be edible, but are not highly regarded, except for the rather large Laccaria ochropurpurea. However, most of the species in the genus, including some of those that may be mistaken for

L. laccata, have not been evaluated for edibility. There is also some evidence that Laccaria species accumulate heavy metals. For example in the aftermath of the nuclear accident at Chernobyl, Laccaria amethystina was found to be quite high in radiocesium (A.R. Byrne, 1998. Radioactivity in fungi in Slovenia, Yugoslavia, following the Chernobyl accident. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 6(2): 177-183. doi:10.1016/0265-931X(88)90060-4); in contrast, L. bicolor and L. laccata were found to be moderate to low accumulators compared to other EM fungi in a Japanese study (Yoshida & Muramatsu, 1994. Accumulation of radiocesium in basidiomycetes collected from Japanese forests. Science of The Total Environment 157:197-205. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(94)90580-0).

This month’s co-author is Dr. Todd Osmundson. Todd is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. His current research (with Drs. Matteo Garbelotto and Sarah Bergemann) involves discovering fungi on the Pacific island of Moorea using field collections and environmental DNA samples. He also works on the systematics of the boletes (Ph.D. at Columbia University and the New York Botanical Garden with Dr. Roy Halling) and did his M.S. research with Dr. Cathy Cripps at Montana State University on Laccaria species in the Rocky Mountains above treeline.

This month’s co-author is Dr. Todd Osmundson. Todd is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. His current research (with Drs. Matteo Garbelotto and Sarah Bergemann) involves discovering fungi on the Pacific island of Moorea using field collections and environmental DNA samples. He also works on the systematics of the boletes (Ph.D. at Columbia University and the New York Botanical Garden with Dr. Roy Halling) and did his M.S. research with Dr. Cathy Cripps at Montana State University on Laccaria species in the Rocky Mountains above treeline.

If you have anything to add, or if you have corrections, comments, or recommendations for future FotM's (or maybe you'd like to be co-author of a FotM?), please write to me at

This page and other pages are © Copyright 2010 by Thomas J. Volk, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.